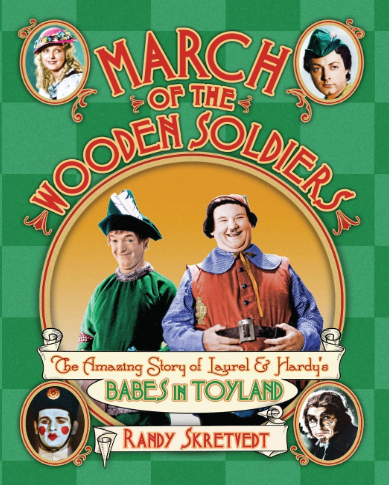

Randy Skretvedt on Babes in Toyland. A Labour of Love

The love is in the detail. Randy Skretvedt tells you not only everything about Babes in Toyland (1934), but also everything about previous and subsequent imaginings of Victor Herbert’s operetta as well as everything about hypothetical versions of this film that might have been made but weren’t.

If you had ever wondered about the subsequent life trajectories of every single member of the cast and crew of this film , then Randy Skretvedt will satisfy this curiosity too.

Hal Roach spoke of this film as the beginning of the end of his relationship with Stan Laurel. Skretvedt has nothing but respect for Roach but does not find corroborative evidence to justify any peculiar bitterness between Laurel and Roach during this shoot. The filming was interrupted by Stan’s most expensive divorce (the romantic life of Stan Laurel was baffling in its complexity) and by both strategic and real injuries.

Skretvedt will also explain the complex reason why this film is known by two titles. Actually, it’s had three titles. Certainly in the United States, this film has a reputation as a seasonal televisual family treat second only to Wizard of Oz. It never quite got that reputation on t’other side of the Atlantic, although it certainly informed my childhood.

There’s something about knowing that the guy who played the villainous Silas Barnaby (Henry Brandon (born Heinrich von Kleinbach) was only 22 at the time that changes your view of the film forever. You can never not see him as a young man playing old. Of course, a real sixty eight year old is unlikely to have been able to play this kind of Barnaby in any case. When Barnaby finally gets into a proper fist fight with the young romantic lead Tom Tom (Felix Knight) it looks like a very even contest. But this is part of the horror of Barnaby – he has all the grasping bitterness and negativity of a version of old age with all the vitality of a young man.

Skretvedt is of course the greatest living Laurel and Hardy chronicler. What Mark Lewisohn is for the Beatles, Skretvedt is for Stan and Ollie. He is sometimes exasperatingly slow to make value judgements. Of course he loves the boys and their films, but his love expresses itself within the painstaking scholarly detail rather than in terms of exclamatory applause. The love is all in the labour.

Skretvedt reports that Stan always wished the film had been shot in colour. He also reports that the set was designed and painted in the hope that it might be. From my point of view, therefore, this film tests my absolute non-tolerance when it comes to colourised movies. As a point of tedious and relentless principle, even if a film-maker expresses a wish that a black and white film could have been made in colour, it is still absolutely wrong to colourise that film, because design choices would have been made on the basis of what the film would have looked like in black and white. And costume choices. And lighting choices. Sometimes even casting choices. Clearly, if Babes in Toyland was designed with colour in mind then if any film is to be colourised it is this one.

Should I bend on this point and tolerate the colourised version? I should not. I should remain absolute. The prospect of a generation growing up with no appreciation for black and white cinematography is a cultural tragedy of such immense proportions that my heart breaks just thinking about it.